Research at Caltech

Research at Caltech looks different for every student, and can often vary term by term. As a chemistry major, my course requirements are on the lighter side for a Caltech major, and many chemistry majors take advantage of the lighter course load to join research groups. This can be whenever the student wants, but many people join labs during their freshman or sophomore years. Some may work in one lab only, and some may switch between labs during the course of their undergraduate studies, depending on if their interests change.

I’ve worked in the Stoltz Group for the entire time that I’ve been at Caltech. The group conducts research in total synthesis and methodology development, meaning we synthesize small molecules from even smaller building blocks, and develop new reactions that have never existed before. Sometimes, the incentive to develop a new reaction comes from the lack of an existing transformation that would be helpful for the synthesis of a molecule. Other times, the development of a new reaction might open up the door to synthesize another molecule that hadn’t been considered before.

Depending on my course load during different terms and even within different weeks of a single term, I might spend more or less time in lab each week. In the past, this has ranged from less than 10 hours to close to 30 hours during the school year, and summer is another story altogether. In this current term, my lab schedule is on the lighter side of this spectrum. Between classes and a senior thesis in history, free time to go into the lab has been a bit tight. Nonetheless, it’s still possible to get work done.

This term, a typical day in lab starts around 8:30 AM. When I get into the office, I write up reaction conditions in my notebook, then head into the lab.

Figure 1. A picture of my lab bay in the morning featuring one of my favorite things about the lab, the floor to ceiling windows!

Figure 1. A picture of my lab bay in the morning featuring one of my favorite things about the lab, the floor to ceiling windows!

Figure 2. Lab coats because lab safety is important.

Figure 2. Lab coats because lab safety is important.

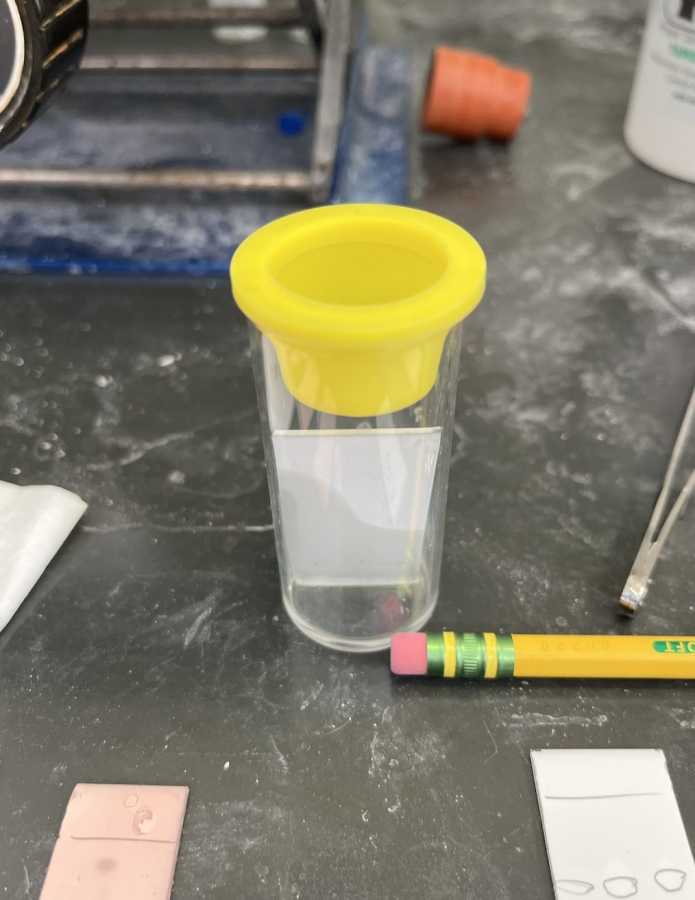

Today, I was setting up a reaction. This involves flame drying a flask (with a blowtorch!), weighing out (air-sensitive) materials in the glovebox (a closed environment containing nitrogen instead of air), and setting up a proper heat source for the reaction. When heating a reaction to the boiling point of a solvent, it’s also necessary to make sure the solvent doesn’t boil off, so the reaction flask gets topped with a reflux condenser (shown below).

Figure 3. Reaction with a reflux condenser! We work with a lot of glass equipment and have to be pretty careful at times.

Figure 3. Reaction with a reflux condenser! We work with a lot of glass equipment and have to be pretty careful at times.

As the reaction progresses, I monitor it by thin layer chromatography (TLC). This involves taking up tiny aliquots of the reaction mixture in a glass capillary tube, spotting the mixture onto a silica plate, and placing the silica plate such that the solvent (in this case, a mixture of ethyl acetate and hexanes) can run up the plate. The results can be seen under UV light, or using various stains.

Figure 4. A TLC plate in a TLC chamber.

Figure 4. A TLC plate in a TLC chamber.

Unfortunately for me, this reaction didn’t work, and that was all the time I had in the lab today.

The next day, I was able to come in and set up the reaction again. Happily for me, the reaction worked well this time! After running a reaction, there’s a series of purification steps to go through, before acquiring a clean product. Usually this involves quenching any excess reagents in the reaction (usually with some aqueous mixture), separation/extraction of the mixture (separating organic and aqueous solvents) to obtain an organic mixture, concentrating the organic solution, and running a silica column to separate any organic impurities. The separation/extraction and column steps are the most crucial for purification. The purified product can be concentrated down, and tested by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for verification. I would hate to have isolated the wrong product!

Figure 5. A rotary evaporation device, or rotovap for short. Used for concentrating solvents down. They get a lot of use in organic chemistry labs.

Figure 5. A rotary evaporation device, or rotovap for short. Used for concentrating solvents down. They get a lot of use in organic chemistry labs.